«Ognuno sta solo sul cuor della terra

trafitto da un raggio di sole:

ed è subito sera.»

(Everyone is alone in the heart of the earth

pierced by a ray of sunshine:

and the night soon comes)

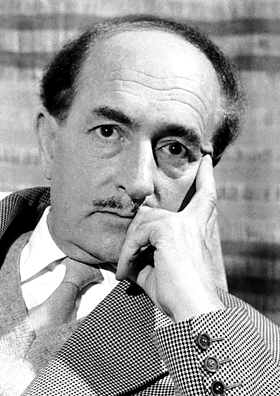

Salvatore Quasimodo (Modica, 20 August1901 – Napoli, 14 June 1968)

Salvatore Quasimodo is considered one of the greatest poets of the 20th century. In 1959 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. His poetic work is framed in the prestigious literary current of hermeticism, inaugurated by two other great men of letters Giuseppe Ungaretti and Eugenio Montale, to whom we must add Alfonso Gatto and Mario Luzi and the French Mallarmè, Rimbaud, Valery and Verlaine. The synonyms of hermetic (source: Treccani) are: arcane, enigmatic, mysterious, obscure. The poetic language therefore abandons the comfortable shelters of the display of erudite words and the romantic escape from reality to venture into the search for the essential word and the perfect synthesis of the poetic message, only apparently cryptic. The inspiration was born in a century dominated by two world conflicts.

The First World War took place in the trenches transformed into the slaughterhouse of an entire generation that fell victim to the degeneration of nationalisms. The Second World War was fought against “absolute evil”, resulting from racial hatred towards the Jews and from an unhealthy will to redeem a defeated nation. The legacy of that massacre was a weak Europe divided by the “iron curtain”. A gloomy atmosphere, dominated by loneliness, indifference, irrationality, immobility. This is how Quasimodo’s masterpieces are born, such as the short poem in the epigraph to this text, which bears a message of shocking relevance: Man is alone, unable to react to the malaise that is surrounding him. He is struck by a ray of that Light which should illuminate minds and warm hearts, but it is too late, darkness marks his inexorable destiny.

“E come potevamo noi cantare

con il piede straniero sopra il cuore,

fra i morti abbandonati nelle piazze

sull’erba dura di ghiaccio, al lamento

d’agnello dei fanciulli, all’urlo nero

della madre che andava incontro al figlio

crocifisso sul palo del telegrafo?

Alle fronde dei salici, per voto,

anche le nostre cetre erano appese”.

(And how could we sing

with the foreign foot above the heart,

among the dead abandoned in the squares

on the ice-hard grass, to the lament

of lamb of the children, to the black scream

of the mother going to meet her son

crucifix on the telegraph pole?

At the branches of the willows, by vow,

even our zithers were hung up)

The second poem quoted above is an implacable indictment of the poet against the absurdity of armed struggle between peoples. Facing the destruction of human values, Quasimodo is forced to renounce his lyrical “weapon” to lean it on the branch of a weeping willow while the blind and murderous fury of criminals in uniform rages and women mourn their children, slaughtered and nailed like Christ.

We cannot avoid placing it in the present day, in a tormented land located in the heart of Europe where, by means of military power, an attempt is being made to overwhelm the force of reason and the right of a people to live in peace and freedom.

NOTE Salvatore Quasimodo was initiated into Freemasonry on March 31, 1922, at the age of twenty, at the Lodge. “Arnaldo da Brescia” of Licata, the same frequented by his father Gaetano, stationmaster of Modica. His decision to join Freemasonry was not known to the family, but it was never officially disowned

IT

IT